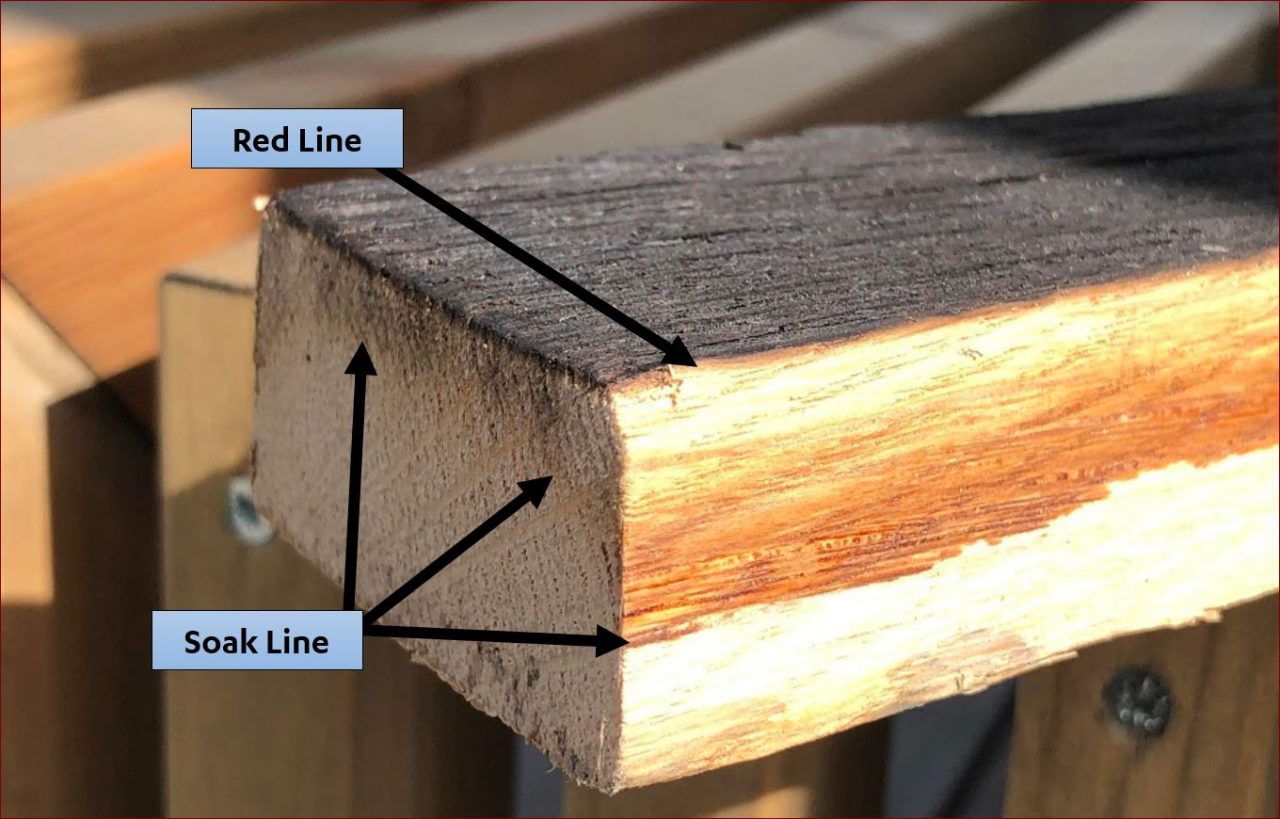

This post is a little longer than normal, but we also got a lot of ground to cover; When you have read this post, you will have learned about barrel charring basics, why it improves whiskey, what the different char levels are, what the difference between the red line and the soak line is – and what happens inside the wood itself, when it gets charred.

If you like this post, please follow me on Instagram (the_bourbon_nerd) and please feel free to leave any comments, corrections, etc. here on the Bourbonr blog or in the FB group.

Whiskey Barrel Charring

Barrel charring is probably one of the most exciting and spectacular things you will come across, as you learn more about American Whiskey. It is unclear how it all started – and there are a lot of interesting theories out there. The most famous one is probably about the Baptist Minister Elijah Craig and the lightning in his barn that accidentally charred his barrels, during the ensuing fire. The story is very likely not true – but it would have been SO cool if it had. The theory that I believe in the most, is that barrel charring simply started because they were trying to remove the smell, of what had previously been in the barrels. You know .. salted fish, oil, and other goodies …. Bourbonr Note: Check out Fred Minnick’s Bourbon Curious for more on this subject.

But … this is a nerdy post – and not a history post – so if you are interested in the historical aspect, you can knock yourself out on Google, I guess – or buy one of the great books about American Whiskey.

What happens inside the wood is basically insane – and you can read about the details below.

By law, many of the American Whiskey types must be aged in new charred oak barrels (technically “containers”, but everybody uses barrels). You char the barrels on the inside using flames, obviously, and some use a gas burner, and some use a “natural” furnace, based on left-over wood from the manufacturing process.

Even though it is not actually an official scale, most manufacturers work with so-called “char levels”, and the consensus is, that the wood is burned as follows:

- Char level #1: 15 seconds

- Char level #2: 30 seconds

- Char level #3: 35 seconds (some go to 45)

- Char level #4: 55 seconds

Level #4 is sometimes referred to as “alligator” char, as the wood looks like the back of an alligator after those 55 seconds – as you may be able to spot from in the picture above. In principle, the scale goes beyond level #4, and there was a famous example of this a few years back when Buffalo Trace released one of their experimental bottles with a level #7 char. According to them, they had charred those barrels for a whopping 3-3½ minutes:

Is longer charring better, then? That very much depends on the flavor/taste profile you are seeking out. Think of charring as a kind of seasoning. Is more seasoning in your food better? That answer will also vary from person to person. Most companies, however, tend to prefer the higher char levels – and as you will read later, there are good reasons for that.

So far, so good. Let’s dig one step further.

There are basically four main reasons why whiskey benefits from barrel charring:

It brings color to the new whiskey that comes from the distillation. You may already know that new whiskey (white dog) is completely clear, and while the liquid will take color from a barrel that has not been charred – charring helps immensely with the coloring.

It increases the surface of the wood inside the barrel. If you look at the alligator char example above, you can clearly see why there is more surface, compared with flat staves. Increased surface means that there are more entry points for the whiskey to interact with the wood.

It “prepares” the wood. Just like barrel toasting (which I will cover in an upcoming post), charring changes some of the chemical compounds within the wood. The three primary compounds in oak wood are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. And while cellulose remains largely unchanged during heat variations, the others change significantly. Hemicellulose will tend to convert into wood sugars – and it is from these special sugars you get some of the classic notes like caramel and toffee. Lignin breaks down into vanillin, which is where the vanilla notes come from.

It draws the natural sugars closer to the liquid. When the sugars in the wood meet extreme heat, it will push those sugars towards the heat source which, in turn, will cause the sugars to caramelize. Caramel is much tougher to burn through, and this is Mother Nature’s way of protecting the wood – and this exactly what you see in nature with living trees. Amazing. Why is this important? Read on for our final deep dive.

read more